Bruhn, Katherine. “Review: Adam de Boer’s ‘Traveller’s Palm’ at Hunter Shaw Fine Art, Los Angeles CA,” Asian Diasporic Visual Cultures And The Americas 6, 2020, pp 184-186.

In today’s global contemporary art world, perhaps more than ever before, artists have the ability to traverse borders, deconstructing and (re)creating identities that are rarely bound to constructs such as nationality. The processes of negotiation that occur as a result of such lived realities are in turn, central to the production of artworks which, in line with the thinking of Homi Bhabha, enunciate from a Third Space: culture’s hybridity. In doing so, they demonstrate Bhabha’s argument that “the meaning and symbols of culture have no primordial unity or fixity” and that “signs can [and should] be appropriated, translated, rehistoricized and [constantly] read anew.”1 Taken as a framework through which to read Adam de Boer’s hybrid practice and recent mixed media body of work, Traveller’s Palm, Bhabha’s oft-cited aphorisms ring true. They are exemplified by de Boer’s ongoing exploration of his own hybrid identity as a first-generation Indo-American or Dutch-Indonesian-American raised in Southern California, and what he refers to in his practice as the (mis)appro- priation of cultural forms.

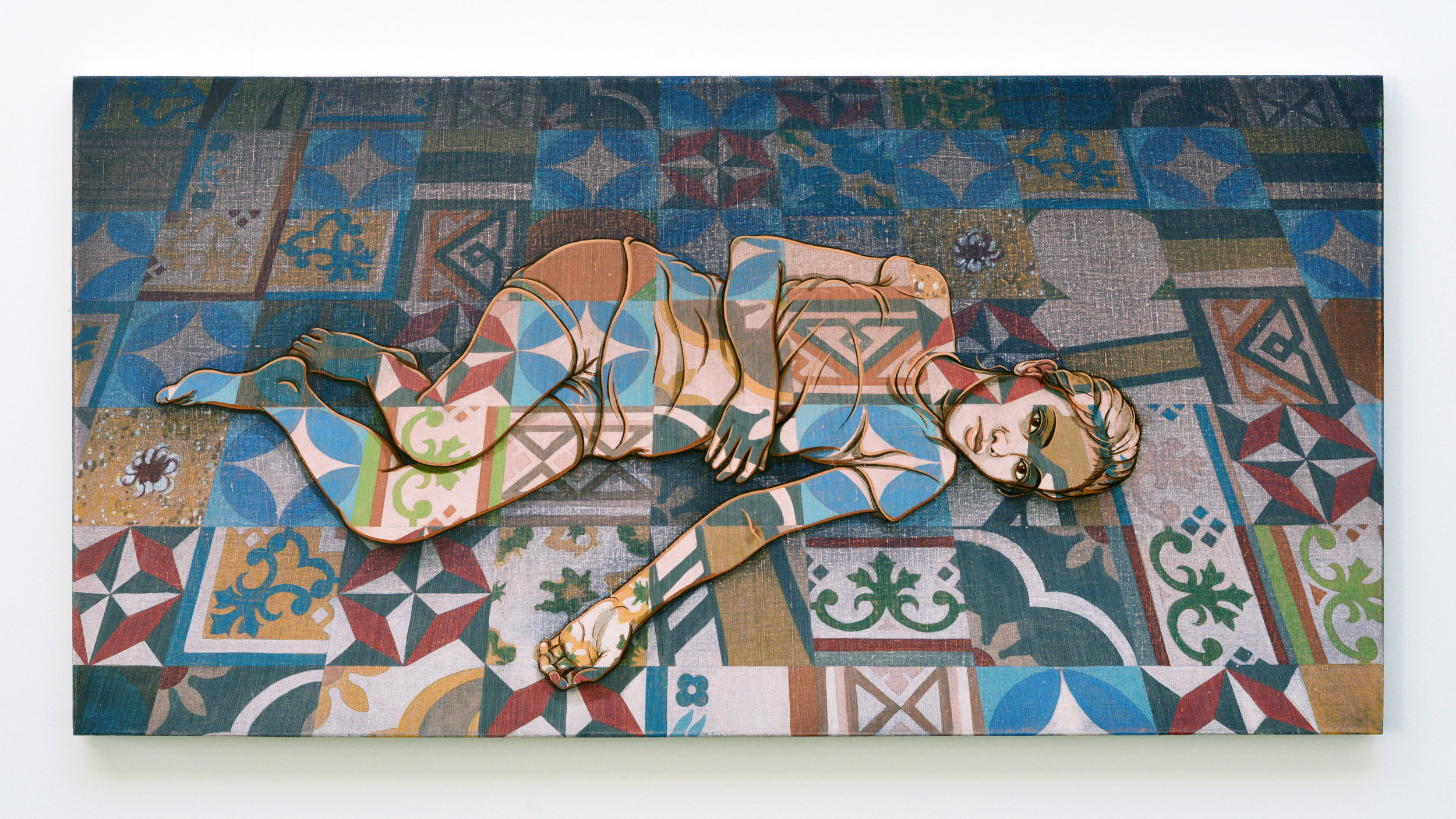

De Boer’s father was born in the Central Java town of Purwokerto to Indo parents who shortly after his birth were forced from Indonesia and into a precarious search for a new “homeland;” a situation that confronted numerous populations who were repatriated to Europe following the independence of Europe’s colonies in Asia and Africa. Eventually settling in the environs of Los Angeles, part of a miniscule Indo-American diaspora, de Boer’s grandparents set aside their tropical roots. Because de Boer’s father was too young to remember his time in Southeast Asia, his memories of this place were not transmitted to his children. The result was what de Boer describes as a decidedly American upbringing. It was not until 2010, during a surfing trip to Indonesia that de Boer’s own interest in his Eurasian roots was sparked. Since this fortuitous journey, de Boer has spent considerable time in Indonesia, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar in the cosmopolitan artist hub of Yogyakarta. As revealed by works like Riana as Ontosoroh (above), this experience has given de Boer the space to develop his knowledge of Javanese craft traditions as well as his own understanding of what it means in the global era to stake claim to identities and create legacies that are both real and imagined.

As is the case with each of de Boer’s works, the final product is the result of a process of layering both in terms of materials and the historical references they point to. In Riana as Ontosoroh, the viewer is presented foremost with the image of a young woman who is at once central to, yet subsumed by, the patterned backdrop that she is placed on. A recurring theme throughout de Boer’s work, these geometric motifs are our first reference to de Boer’s unique play with cultural signifiers. Called “tegel tiles” such brightly coloured cement tiles are prevalent in contemporary design today. In Yogyakarta, especially, they are used to decorate the innumerable cafes frequented by Indonesia’s ever-growing middle class. However, they are not Indonesian or even Dutch despite the fact that tegel is the Dutch word for tile. Rather, they are English in origin and were introduced to Indonesia via Portugal by the Dutch in an effort to bring hygienic surfaces to the colonies. Further transformed by de Boer, they are remade through his use of the Indonesian craft tradition batik, or wax-resist on linen cloth, that, instead of premade canvases, serve as a base for many of his mixed-media paintings.

Returning to the figure that rests on top of these tiles, varied interpretations are no doubt possible. The model is positioned in a way that portrays a certain vulnerability: lying on her side with one arm opened, Riana is exposed to the viewer’s gaze. Yet, staring directly at the viewer she is unapproachable, thus becoming Nyai Ontosoroh, the protagonist in Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s This Earth of Mankind (1980). Written in jail when Toer was a political prisoner, the epic novel, set in 1898, is about the Native wife of a Dutchman during Indonesia’s colonial era. Although Nyai Ontosoroh is a concubine, she is self-made, tough, and most significantly, turns notions of female subjugation on their head. In conversation with de Boer, he explains that while he uses models who he does in fact know, like Riana and even himself, he is not interested in the mere depiction of an individual’s likeness. Instead, he is concerned with the ideas, or in this case the archetypes, that such representations might portray. In this way, Riana as Ontosoroh is intended as a comment on the resilience of Indonesian women specifically and Indonesian society generally, themes that arguably can be extended and reapplied to varied contexts globally.

As such, despite what is de Boer’s explicit reference to Indonesian culture and its colonial past, it is unsatisfying to draw simplistic conclusions as to the intent or function of any one work part of his repertoire. Riana as Ontosoroh is no doubt a reflection of de Boer’s ongoing interrogation of his own hybrid identity while it also functions as a commentary on the appropriation of aesthetic and material traditions. Through his unlikely synthesis of seemingly contradictory elements like oil paint on batik, de Boer successfully produces objects that challenge what we expect from contemporary art. While some have accused de Boer of exoticizing Indonesian tradition, we must ask, who in fact has the right to these traditions? To conclude where we began, I reaffirm the idea that “the meaning and symbols of culture have no primordial unity or fixity”2 and thus de Boer either through his identification with his Indo heritage or simply because he like many others has travelled to Indonesia, has a right to claim or read anew the symbols that constitute a contemporary global culture.

Katherine Bruhn

University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA

katiebruhn@berkeley.edu

Katherine Bruhn is a PhD candidate in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Her dissertation examines connections between the positioning of Minangkabau artists in Indonesian art history and ways in which they have negotiated contradictions related to local custom and Islam over time.

Reference

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

1 Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 37–38.

2 Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 37.