Molly Surazhsky

Mashacare: Home of the Freaks, Misfits, & Weirdoes

Opening reception and fashion show:

Sunday July 14, 6-9pm

On view:

July 14 - August 18

Gallery hours:

Thursday - Sunday 11am - 5pm and by appointment

5513 W Pico Blvd. Los Angeles CA 90019

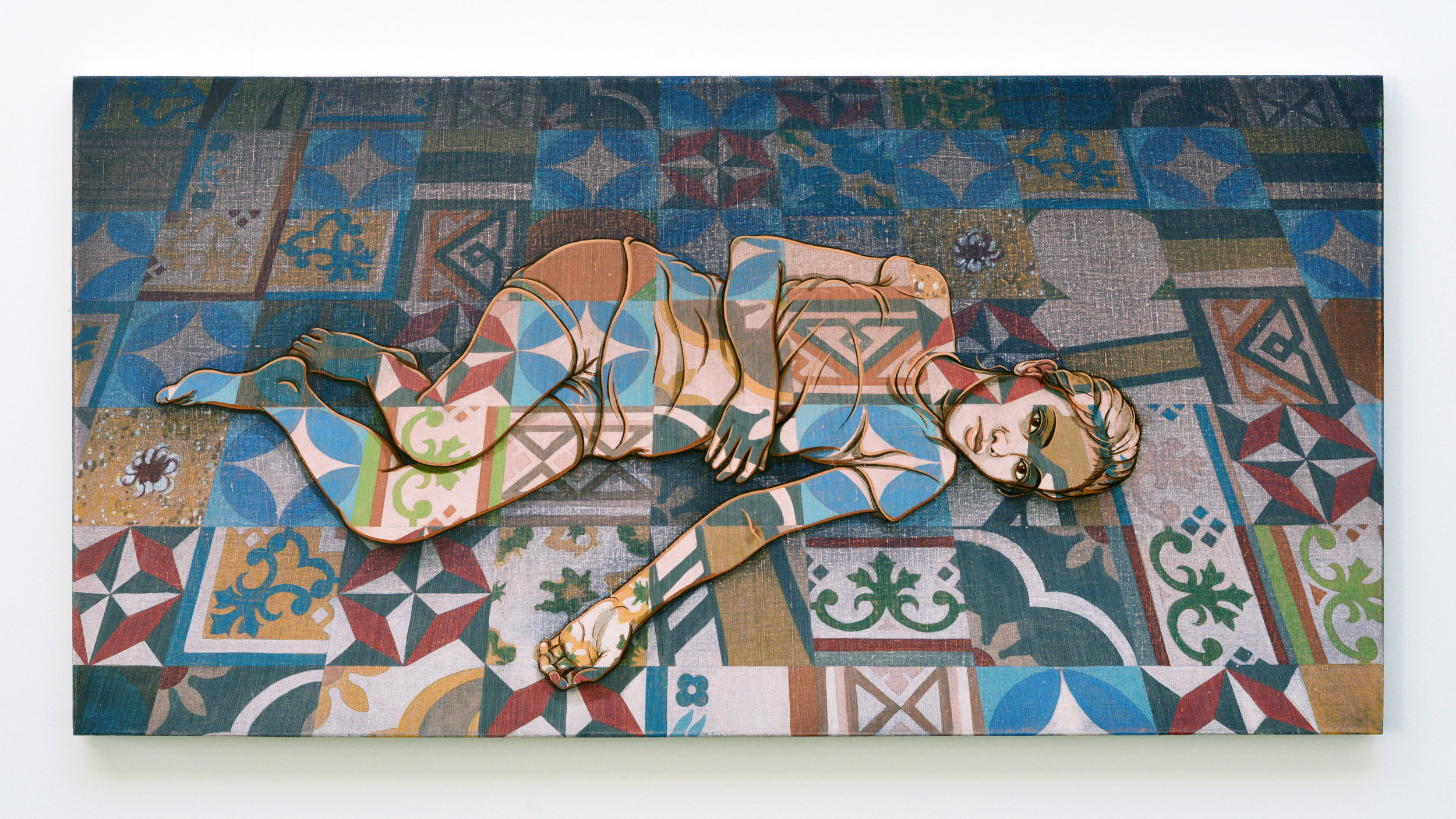

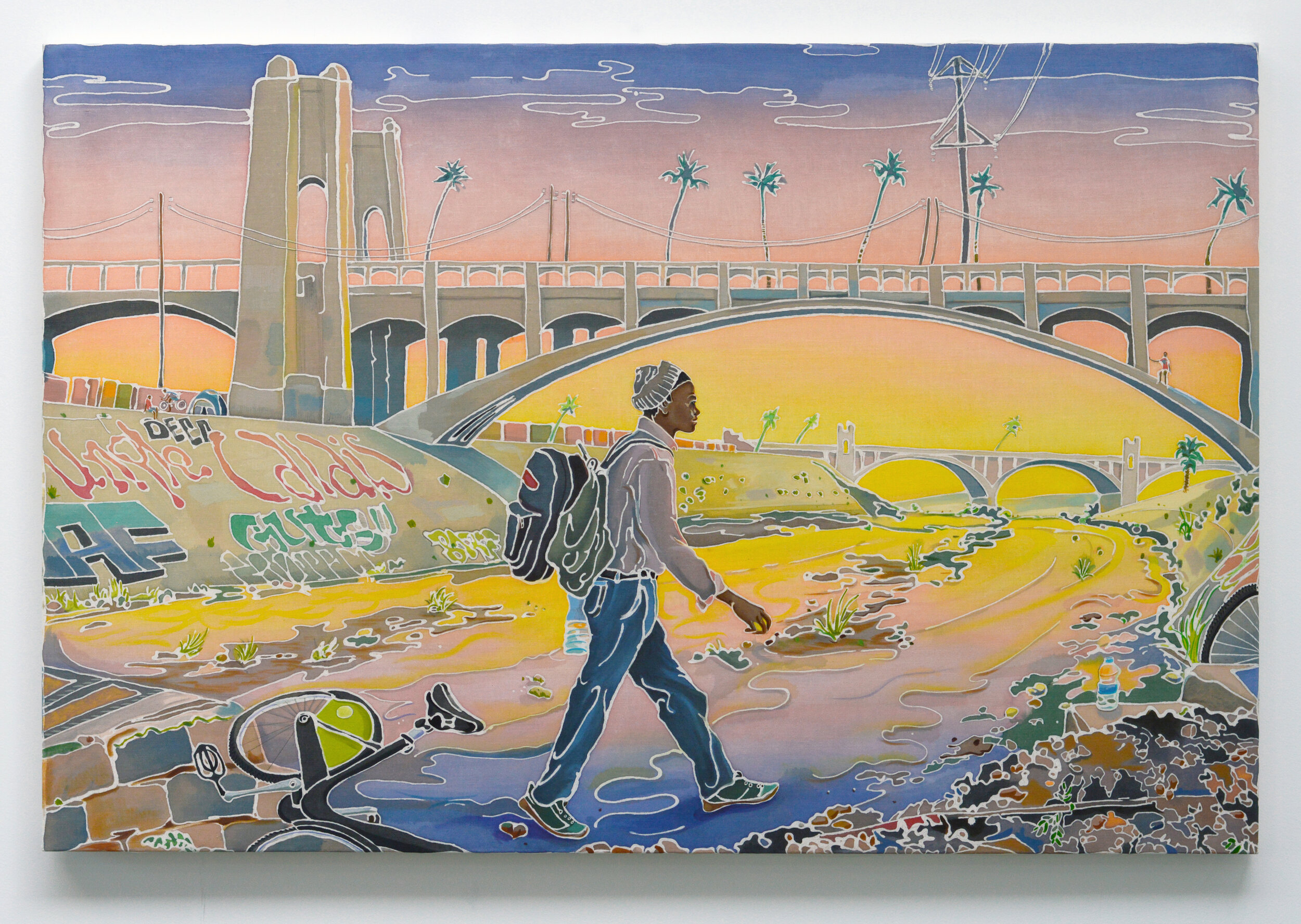

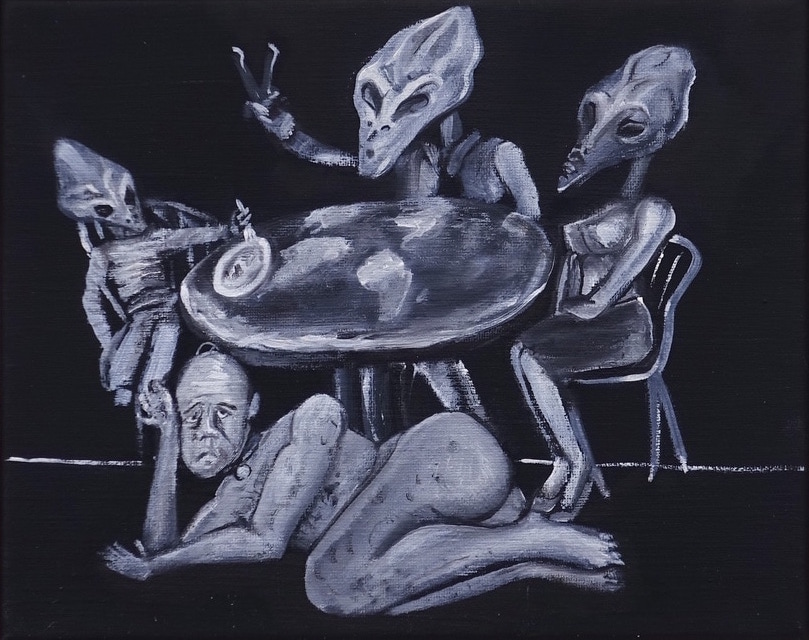

Hunter Shaw Fine Art is pleased to present Mashacare: Home of the Freaks, Misfits, & Weirdoes, the gallery’s first solo exhibition with Molly Surazhsky. On view is the culmination of a multi-year project which utilizes sculpture, sound, photography, textile design and handmade garments to articulate a detailed science fiction narrative involving themes of healthcare, identity, survival and global warming. Channelling Varvara Stepanova and Lyobov Popova, the artist’s heroes of the Constructivist movement, Surazhsky uses textile design and garment-making to envision the inhabitants of a new world. While the Constructivists were working to reimagine their society within the pretext of a hopeful revolutionary spirit that shook their entire nation, Surazhsky produces work in more cynical times, therefore choosing to invent an entirely new place: the floating city of Mashacare, a tiny utopia adrift in the dystopian seas of a post-melt waterworld.

Mashacare’s internal narrative begins in the present as the Earth’s rising sea levels coincide with the rise of corrupt, right wing governments worldwide. Around this time, Masha, a Russian Babushka in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn begins holding free healthcare and wellness training sessions for women in her community, a service that will grow in popularity and necessity as the poor are gradually stripped of basic necessities including housing, daycare, education, and, of course, healthcare. As Mashacare gains attendance, a vast archive of sustainable, affordable, and comprehensive remedies is established, and from that grows a truly renegade healthcare system: hundreds of women running free clinics from their homes across the nation, and eventually the world. Annual panels are held amongst practitioners, and a physical archive and education center is created in Brooklyn to house remedies, samples and case studies. The organization is at first treated as a major threat by Big Pharma and the Establishment, but as decades of ecological collapse ensue, the elite turn their focus to a new project: creating home elsewhere in the cosmos. In the final years of land access, the Mashacare community bands together using their collective skills to terraform an artificial island from available materials, while democratically creating a peaceful and matriarchal social structure. Existing under continual threat of airborne plagues issuing from nearby cesspools of floating plastic and trash, the island’s inhabitants live with Mashacare’s original holistic healthcare philosophy at the core of their society. By 2100 AD, Mashacare is thriving with sectors dedicated to architecture, farming, healing, engineering, and love. With the flooding of the Earth came the end of patriarchy, the end of capitalism, and the opportunity to start fresh.

Deftly interweaving utopia and dystopia, fact and fantasy, personal and political, Surazhsky communicates with a sophisticated command of materials across a diverse range of media. Sustaining the tradition of women in her family who have worked as tailors for generations, Surazhsky’s sculptural works are comprised of posed mannequins and dress forms outfitted in one-of-a-kind, hand-tailored garments. These pieces often feature transparent plastic pockets containing various medicines and wellness products, complimented by colorful textiles designed by the artist. Expressing the visual culture of Mashacare, Surazhsky’s bold textiles are collaged from sources significant to the project including stock images of herbal remedies, appropriated Constructivist patterns, emojis, maps and family photos. One image features a group of women from Surazhsky’s family - including her grandmother Masha, the project’s eponymous matriarch - engaged in a celebratory dance. Above the joyous photo, on a backdrop of high-visibility orange, a black text states, “Mama, we eradicated: illness, violent men, trash, money, misogyny, heteronormativity, xenophobia, homelessness, weapons.”

A shrewd political sensibility and sharp sense of humor are evident throughout the body of work which plays with the visual language of both political propaganda and corporate branding. This inclination is further expressed through the show’s exhibition design which features vinyl wallpaper, fashion photography and audio narration. An underlying cynicism manifests in a deeper questioning of the traditional “art object,” its production, marketing, and sale to a mostly elite consumer base. Bringing mannequins and clothing into the space of an art institution, Surazhsky challenges the cultural hierarchies between art and fashion which presume that art and artists hold a higher moral ground when compared to other industries. Unlike art, fashion is regularly recognized for its blatant misdeeds and commodity status. Accordingly, Surazhsky presents the viewer with what could more directly be classified as commodities within the gallery space. On the other hand, Surazhsky’s work brings the labor of tailoring out from behind the scenes, highlighting the craft of couture as an artform and occupation dying in the age of fast fashion. Directly informed by Surazhsky’s upbringing in an immigrant, working class family who left the Soviet Union with communal tendencies intact, Mashacare combines a collective, utopic cynicism with an ode to the invisible labor of women, whether it is sewing or caregiving. The results are a complex and multivalent body of work articulating a vision of queer, feminist populism that feels refreshing, necessary and achievable in spite of austere predictions for our future.

Molly Surazhsky received a BFA from California Institute for the Arts, Valencia CA (2019) and attended Mountain School of the Arts in Los Angeles, CA (2017). Recent exhibitions include Mashacare: Home of the Freaks, Misfits & Weirdoes (thesis exhibition), A402 Gallery, CalArts, Valencia, CA (2019); Death Show, Elevator Mondays, Los Angeles (2018); EX NIHILO, Elevator Mondays, Los Angeles (2018); CO/LAB III, Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA (2018); and El Acercamiento, Fábrica de Arte Cubano, Havana, CU (2017).

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

In conjunction with the opening reception, there will be a live fashion show presenting the complete Mashacare collection of 21 unique looks. Models include: Abigail Stanton, Alicia Piller, Anais Franco, Finn Hopper, Herbert Mendoza, Isabel Ivey, Jasmine Alise, Jordan Terrell, Kat Walker Shea, Kristin Wetenkamp, Lindsey Villarreal, Melis Nur York, Michelle Sauer, Richard Chevrier, Samara Bradley, Serena Himmelfarb, Shaun Johnson + Fanny, Tatiana McClung, Violet Sciole, featuring music from DJ Charlie Scovill and Lighting Design by Soowan An.

The artist would like to acknowledge Courtney Coles for co-producing the photographs, as well as voice actress Abigail Stanton and coder Taeheem Kim for their work on the sound pieces. A tremendous thank you to Natalia Surazhsky, Shane Rothe, Shaun Johnson, Violet Sciole, Milan Northcote, Alicia Piller, Finn Hopper, Isabel Ivey, Anais Franco, and Tatiana McClung. And finally, a very special thank you to Scott Benzel for his continued support.